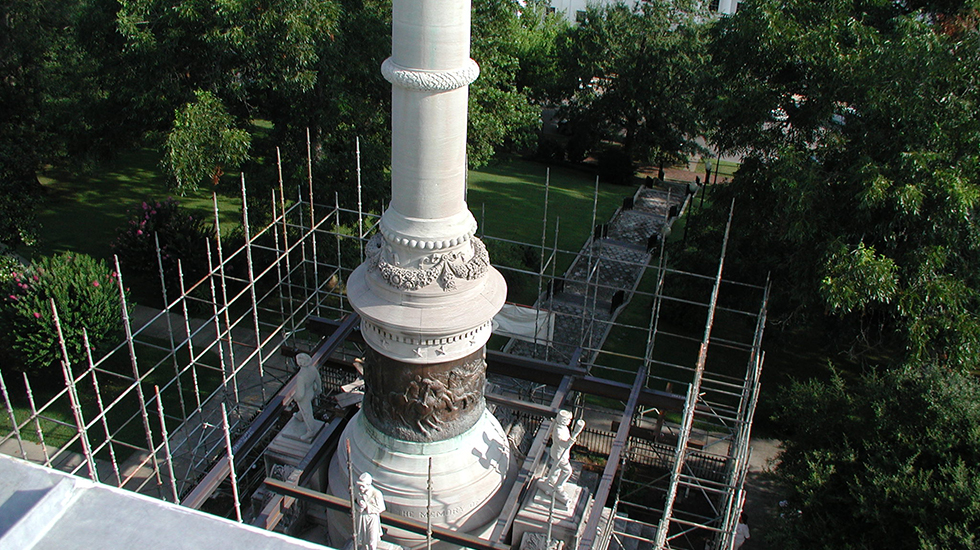

The State of Alabama contracted with McKay Lodge Conservation Laboratory, Inc. through the Alabama Historical Commission to undertake a condition study of their Confederate Monument that was built over many years beginning in 1886. The tall limestone monument stands just outside the north entrance of the capitol building.

In its proposal, the lab offered to provide a comprehensive study in the form of a standard Historic Structure Report. The submitted report results from on-site assessments of the materials, structure and condition of the Confederate Monument at the Alabama State Capitol along with substantial historical research, field trips and consultations associated with the aims of the assessments. A team was assembled by McKay Lodge, Inc. to address the various facets of the Confederate Monument Preservation project. Robert Lodge, a member of the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI), undertook documentation and specifications writing as well as microscopy; Dr. Michael Panhorst, a sculpture historian, researched the monument¹s history; and conservator Thomas Podnar took charge of issues pertaining to bronze and stone. Dr. Bruce Simonson of the Oberlin College Department of Geology lent his considerable expertise in limestone.

The assessments and associated historical research presented within the Historic Structure Report form a comprehensive information project solely devoted to a goal of preservation of the Confederate Monument for the future.

The comprehensive project comprised two major phases: an Existing Conditions Survey (this includes the condition assessments and the associated historical research) and a resulting Historic Structure Report. The design of this project, its activities and report, closely follow the plan recommended in the cooperative publication of the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) and the Association for Preservation Technology International (APT): Guide to Preparing Design and Construction Documents for Historic Projects, Publication TD-2-8, 1996.

The Historic Structure Report containing information on the current physical state of the monument and historical information on the monument as well as a statement of historical, commemorative and artistic significance of the monument, all work in complement toward preservation. In order to garner interest in preservation of the monument, its significance or value to its public in Montgomery, in Alabama, and in the Nation must be well recognized at the outset. In order to effectively plan preservation measures, its materials, structure and current conditions must be accurately recognized and recorded. It is through this complement that the Historic Structure Report becomes a comprehensive approach to preservation.

The 85-foot tall Confederate Monument on Capitol Hill in Montgomery stands in commemoration of the service and sacrifice of 122,000 Alabamians who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Fund-raising for the $45,000.00 monument began in 1865 and was largely the work of Alabama women, as was typical of memorial patronage in the South. The Ladies Memorial Association raised the money through a lengthy effort involving bazaars and appeals to private donors and the state government. Due to pressing needs of widows, orphans, and Confederate veterans in the Reconstruction South, the cornerstone was not laid until 1886, when Jefferson Davis performed the ceremony with full Masonic rites just a few feet from the spot where he had taken the oath of office as President of the Confederacy.

In 1886 the foundation for the colossal column was in place, but another twelve years passed before the monument designed by Alexander Doyle (1857-1922) was completed with its handsome bronze allegorical finial figure of Patriotism, granite statuary by Fred Barnicoat (1857-1942) representing the four branches of the Confederate armed forces, and a bronze relief band that encircles the column. The elaborate dedication on December 7, 1898 (nearly forty years after the war, the highpoint of its commemoration) was attended by thousands who cheered the lengthy orations, poetry, and pageantry of the Lost Cause.

The Confederate Monument on Capitol Hill is one of the largest Civil War monuments in the South. Indeed, it is comparable in form and scale to many Civil War monuments in northern state capitols and major cities that generally predate it due to the stronger post-war economy in the North. The colossal columnar monument form, the patriotic and military imagery, the stone and bronze materials, even much of the meaning of the Confederate Monument is similar to that of other Civil War memorials—North and South alike.

As with the earliest memorial efforts in the North, the intent of those who met in Montgomery in November 1865 was “to build a monument to the dead.” Over the decades it took the monument to materialize, its purpose was broadened to encompass the service of all those who fought, as was also the case with later Union memorials. Like Civil War monuments North and South, it commemorates the courage and patriotism of those who fought, and especially those who died for their beliefs. Like many Confederate monuments, it acknowledges the South’s intent to secede to defend states’ rights and individual liberties just as the colonies had seceded from Britain a century earlier, and it accepts defeat of the Lost Cause while maintaining manly and regional honor.

Sculptural features of the monument include four granite figures representing the Confederate Navy, Infantry, Artillery, and the Cavalry. These were carved in granite by Fred Barnicoat of Quincy, Massachusetts and installed by Curbow and Clapp, a local monument company in Montgomery.

The top of the monument’s column carries a large bronze allegorical figure of Patriotism, well made and in excellent condition. Patriotism may seem at first an ironic concept with which to cap the Confederate Monument on Capitol Hill. During the war and now, the predominant northern perspective of southerners in the Civil War is that of rebels, traitors to the Union of States. Yet the South saw its efforts at resisting northern domination of internal affairs as comparable to those of this nation’s founding fathers, who declared independence from a foreign power. The South fought for states’ rights of self-determination of issues, including slavery. This principal perhaps survives in the current Alabama State Motto: Audemus Jura Nostra Defendere (We Dare to Defend our Rights) proposed by Marie Bankhead Owen, then director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, for the Alabama Coat-of-Arms designed in 1923 and adopted years later. The outcome of the war established the Union of the states, the federal government, as first and foremost, a higher authority than the individual states. The lower portion of the column consists of a circular limestone plinth bearing the inscription “Consecrated to the Memory of the Confederate Soldiers and Seamen,” including the dates 1861–1865, and the band of bronze capped with a limestone entablature. The band of bronze is a high relief encircling the column’s base. This band of bronze measures over 76 inches high. Each section has cast flanges behind the visible face that allow invisible bolting of one piece to the other. The diameter of the relief is approximately 92 inches. The relief depicting a generalized but accurate battle scene was designed by Alexander Doyle (1857–1922), the designer of the monument, who did the sculpting of the full-size design in clay for the casting. The relief was cast by the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company of New York City which operated under the name E. Henry & Bonnard from 1872 to 1881 and under The Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company from 1882-1926. The bronze bears the date of 1888.

Messieurs Henry and Bonnard ran one of the finest fine arts bronze foundries in the country at that time. The bronze was cast with sand molds, the only casting technique available in the U.S. prior to the introduction of lost wax casting by Roman Bronze Works in the 1890s. Even after the advent of the ancient casting technique, reliefs like these probably would have been cast with sand molds because the thin, flat sections are more easily cast with sand molds than with bulky investment molds needed for lost wax. Fine craftsmanship is evidenced by the absence of porosity and patches in the surface of the bronze and the precise fit of the different sections of the relief.

The band was cast in six sections. Each section has a cast flange to the rear along the joining edges. The tight joins of the bronze follow forms wherever possible. These flanges are bolted together behind the band. This joining technique was revealed when a deteriorated portion of the plinth was cut out to study what was behind the bronze.

An investigation was made during the assessment to determine what was behind the bronze band. Signs of expansion and opening of joins of the metal band at the bottom and top were taken as signs of a possibility there was material behind the bronze that was swelling with water and expanding on freezing. Since the limestone forming the plinth under the bronze was so deteriorated as to leave no doubt it would need replacing, liberty was taken to cut into the most deteriorated stone deeply enough to look up under the bronze. There, red sand and debris from rock (and possibly brick) was found packed within the space left behind the bronze band and the stone drum centered within that bears the load of the column. The sand was dense and firm either from deliberate packing or through settlement. It was important to discover, when access to this space was made during the assessment, that the sand was holding moisture; it was damp even though the monument had not encountered rain for the previous 22 days. The sand has no useful purpose except possibly as an aid in keeping the band centered during construction. It is expected that the band of bronze was assembled on the ground and lifted into place after the stone drum that resides behind the bronze was placed. The bronze band simply rests upon its stone plinth and the stone of the column above places no weight upon the bronze.

It is plainly evident that the monument has two distinctly different looking limestone. The limestone of the base is gray, largely due to the growth of a biofilm, while the limestone used for the column section including the column base is tan. The distinction in color is sharply demarcated.

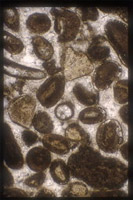

A comparative study of the limestone used for the base with the limestone making up the column section reveals that they do have physical differences that would suggest they came from distinctly different quarries or regions. While the historic records tells only that the limestone came from a quarry in Russellville in the northwestern corner of Alabama, the upper limestone is not characteristic of stone quarried in that area but appears, instead, to be characteristic of limestone from the area of Bedford, Indiana. T.L. Fossick, the owner of the Russellville, Alabama quarry that supplied the stone for the monument, had family that owned a quarry in Bedford, Indiana. The most visible difference to a viewer of the monument is one of color. This is caused by the formation of a black/brown biofilm on the Russellville limestone of the base that is not growing significantly on the upper limestone of uncertain origin. This preferential growth reflects some difference in the stone. Perhaps the smaller crystallization of calcite in the Alabama stone with its greater porosity harbors the nutrients and gases for the lowest level of the food chain for the support of the biofilm.

The differences between the stones are seen on closer scrutiny. When the are cemented together through crystallization, calcite crystals develop or grow in various sizes. The calcite crystals cementing the oolites of the Russellville limestone from the base are small and the oolites are consequently dense in population. In contrast, the calcite crystals cementing the oolites in the limestone of the upper monument are quite large and, consequently, the population of oolites are less dense.

Records tell that the limestone used in the construction of the Confederate Monument, begun in 1886, came from a quarry near Russellville, Alabama. The quarry there was new, having opened in 1884. The limestone came from the early quarry of T.L. Fossick, located about two miles west of Isbel, then named Darlington, south of Russellville in the northwestern corner of Alabama. T.L. Fossick, Sr. came from England before the Civil War and first opened a quarry a few miles west of Cherokee, Alabama. Later, according to a deed in the Franklin County Courthouse dated 1884, Fossick purchased land in Franklin County from the Wood’s family and, with his two sons, opened a new quarry he called “Rockwood,” playing on the name of the Woods family and his stone.

According to a brief history on the Rockwood quarries published in a Russellville historical magazineThe Source, Vol. 8, Issue 2 (October 2000), there was a paper published in 1891 that advertised: “T.L. Fossick Company Oolitic Limestone Quarries. Dimension Stone of Every Kind Furnished on Contract. The Largest Dimension Stone Quarries in the South. Quarries at Rockwood…Two Miles West of Isbel, Franklin County, Alabama.”

The Fossick limestone quarries continued under Fossick under various company names and then under other ownership. Today, quarries in that area continue to produce limestone, some of the finest building limestone in the United States, under the Alabama Stone Company, Inc., a division of Vetter Stone Company, Mankato, Minnesota.

The limestone taken from Rockwood and the larger Russellville area is today marketed as “Alabama Shadow Veined Limestone” because of its veins of darker gray color in a light gray stone. The quality and characteristics remain highly consistent. The same light, cool gray color and some darker veining were evident in a cleaned stone on the base of the monument. A microscopic, comparative study of the base limestone with the apparently different limestone of the column was made in order to identify as precisely as possible how they differ. To complement this comparison, a sample of old Russellville limestone from a block still at the quarry now operated by Alabama Stone Company was taken and compared with the Russellville limestone used in the monument’s base. Also, a known sample of Indiana limestone was examined under the microscope and compared with the limestone from the upper part of the monument. It was found that characteristics of the lower monument stone match characteristics of Alabama limestone, while characteristics of the upper stone match very closely characteristics of Indiana limestone.

It is conceivable that T.L. Fossick arranged the later supply of stone from Indiana. It is possible that only a few at the time knew of this. Many of the stones in the lower monument show sedimentary weaknesses that have led to spalling and crumbling. These faults in the stone were probably evident as early as the period of construction and may have led to a complaint against Fossick’s supply. Fossick’s Rockwood quarry had not been in operation long and may have, at that time, been quarrying close to the surface, taking inferior overburden.

When the stone of the monument is clean, there will still be a visual distinction between the stone. While the black biofilm from the base will have been removed, the Alabama limestone there will show its characteristic color and “blue-gray” veining while the Indiana-type limestone will have its uniform, characteristic tan color. There are issues calling for further study. One is the possibility of residual biocidal control of the growth on the lower limestone. That growth is expected to return. A test of the biocide D/2 developed by MCC Materials, Inc. of Connecticut is recommended after the monument’s stone has been cleaned. Treatment of the stone to lock-out the nutrients and to aid in future cleaning are to be investigated. The product developed by Dr. Norman R. Weiss and Irving Slavid of MCC Materials, Inc. and now marketed as HCT (hydroxylating Conversion Treatment) by Prosoco, Inc. may be a candidate. Work on the monument is expected to be completed during 2002.

Alabama has funded the development of a comprehensive website devoted to the monument, its design, history and preservation. McKay Lodge, Inc. is designing the site with Poseidon Web Solutions of Chicago , the firm that created the public information site for the restoration of the Tyler Davidson Fountain in Cincinnati, Ohio.

WEBSITES:

For more information about the Confederate Monument, go to:

www.preserveala.org